Rao, S1

1Corresponding Author: Sohail Rao, MD, MA, DPhil. HBond Foundation, 6819 Camp Bullis Road, San

Antonio, Texas 78256, USA. E-mail: srao@hbond.orgnd.org

Abstract

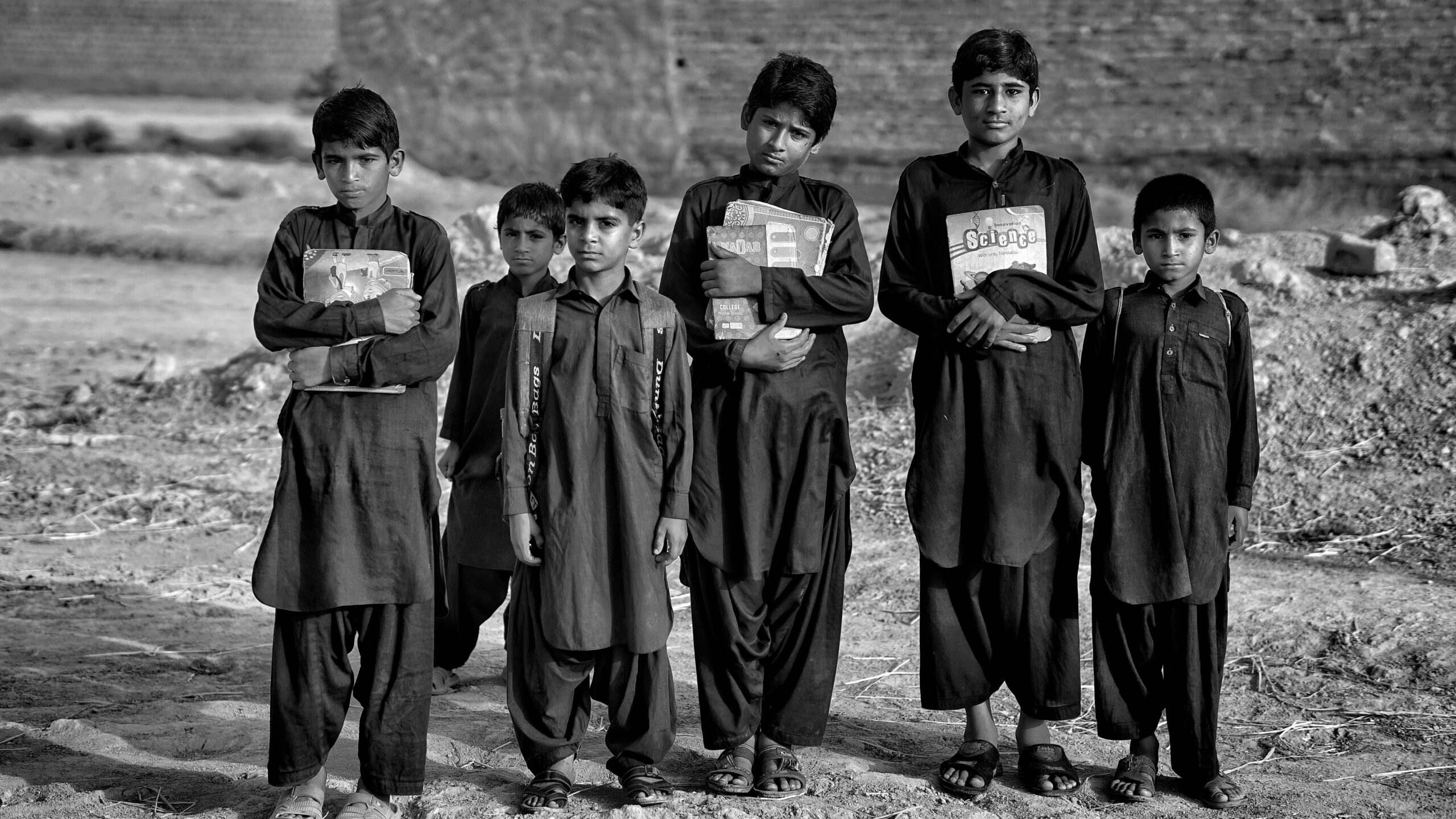

K-12 education is a foundational pillar for Pakistan’s socioeconomic development, directly influencing economic growth, social mobility, and national progress. Despite its importance, the education system faces deeply rooted systemic challenges that hinder its ability to deliver equitable and quality education. Pakistan has one of the world’s largest youth populations, with over 85 million children under the age of 18, yet nearly 23 million children remain out of school, making it one of the highest rates globally. This crisis disproportionately affects girls and marginalized communities, particularly in rural areas where poverty, gender discrimination, and inadequate infrastructure limit access to education. Even for those enrolled, the quality of education is often compromised by overcrowded classrooms, poorly trained teachers, and an overreliance on rote memorization rather than critical thinking or problem-solving skills.

In an effort to address these systemic issues, the Government of Pakistan introduced the Single National Curriculum (SNC) in 2021. The SNC aims to standardize curricula across public, private, and madrassah schools, seeking to bridge educational disparities and provide equal learning opportunities to all students. By incorporating modern subjects such as STEM education, ethics, and critical thinking, the SNC aspires to prepare students for the demands of the 21st century. However, while the intentions of the policy are commendable, the implementation of the SNC has sparked considerable debate.

Critics argue that the SNC’s standardization approach may unintentionally lower the quality of education, particularly in private schools that historically offer more advanced and rigorous curricula. Forcing private institutions to adopt the same curriculum as public and madrassah schools’ risks limiting their ability to innovate, maintain higher standards, or provide specialized programs tailored to diverse student needs. This concern, described as a “race to the middle,” may inadvertently undermine the educational advantages that private schools provide. Additionally, logistical challenges, such as inadequate teacher training, lack of infrastructure, and resistance from madrassahs, present significant obstacles to effective implementation. Without sufficient investments in resources and professional development, the policy risks exacerbating existing disparities rather than resolving them.

This paper explores the multifaceted challenges facing K-12 education in Pakistan, including issues of accessibility, gender inequality, poor infrastructure, and the quality of learning outcomes. It examines the goals and limitations of the SNC, analyzing its potential benefits in creating equity and its risks in homogenizing education at the expense of quality and innovation. Finally, the paper offers recommendations to ensure that the SNC fulfills its promise of equitable education for all, including balancing standardization with flexibility, investing in teacher training, improving infrastructure, and fostering collaboration between the government, private schools, and madrassahs. By addressing these challenges holistically, Pakistan can create a more equitable and effective education system that meets the needs of its diverse student population and prepares them for future challenges.

Keywords: K-12 education, Single National Curriculum, Pakistan education, gender disparity, education reform

Introduction

Education is universally recognized as a powerful catalyst for economic growth, social mobility, and societal

transformation. It empowers individuals to contribute

meaningfully to their communities while fostering

innovation, reducing poverty, and strengthening

governance. For Pakistan, where over 44% of the

population is under the age of 18, the potential of the K-

12 education system to shape the country’s future

cannot be overstated (UNICEF, 2022). A robust

education system not only builds human capital but also

addresses key challenges such as unemployment,

gender inequality, and social exclusion. Despite its

critical importance, Pakistan’s K-12 education system

faces deep systemic challenges that hinder its ability to provide equitable and quality education to all children.

The Constitution of Pakistan, under Article 25-A, guarantees free and compulsory education for all children between the ages of 5 and 16, emphasizing the state’s commitment to universal education (Government of Pakistan, 2012). However, this constitutional mandate has yet to be fully realized, as Pakistan continues to grapple with one of the highest rates of out-of-school children globally. According to recent estimates, nearly 23 million children remain out of school, with girls and children from marginalized communities disproportionately affected (World Bank, 2022). Many of these children reside in rural areas, where access to schools is limited, and cultural barriers further hinder enrollment and retention.

The education system in Pakistan is also characterized by fragmentation and inequality. Public schools, which serve the majority of the population, often lack basic infrastructure, including functional toilets, clean drinking water, and electricity. Teacher absenteeism and outdated pedagogical methods further exacerbate the challenges faced by students in these schools (Pakistan Education Statistics, 2021). On the other hand, private schools, which account for a significant share of enrollments in urban areas, cater primarily to wealthier families and often offer superior resources, infrastructure, and academic rigor. This divide creates stark inequities in access and quality of education, reinforcing socioeconomic disparities. Adding to this complexity is the role of madrassahs, which provide religious education but are often disconnected from the broader goals of academic and professional development (Zafar, 2022).

Recognizing these systemic challenges, the Government of Pakistan introduced the (SNC in 2021. The SNC was designed to standardize curricula across public, private, and madrassah schools, aiming to reduce disparities in educational access and quality while fostering a unified national identity. By integrating modern subjects such as STEM education, ethics, and critical thinking into the curriculum, the SNC aspires to prepare students for the demands of the 21st century (UNESCO, 2022). However, while the policy’s goals are ambitious and well-intentioned, its implementation has sparked debate among educators, policymakers, and stakeholders. Critics argue that the SNC risks homogenizing education at the expense of innovation and flexibility, particularly in private schools that have historically maintained higher academic standards. Moreover, logistical challenges, including insufficient teacher training, resource limitations, and resistance from certain madrassahs, raise concerns about the policy’s feasibility and effectiveness (Ahmed & Ali, 2022).

Challenges in K-12 Education

Pakistan’s education system faces profound systemic challenges that hinder its ability to provide equitable and quality education to millions of children. With nearly 23 million children between the ages of 5 and 16 out of school, Pakistan ranks as the second-highest country globally in terms of out-of-school children (UNICEF, 2022). This alarming figure reflects deep-rooted inequities that disproportionately affect girls an marginalized communities, particularly in rural areas. Societal norms, poverty, and safety concerns are some of the key barriers preventing girls from attending school, with only 52% of girls enrolled in primary education compared to 60% of boys (UNICEF, 2022). For families

“An educated society is the cornerstone of a thriving and just civilization, where knowledge empowers individuals to build a better tomorrow.”

Anonymous

struggling with economic pressures, boys’ education is often prioritized, perpetuating a cycle of gender inequality and social exclusion.

Even for children who are enrolled in school, the quality of education remains a pressing concern. Learning outcomes in Pakistan are alarmingly low, with more than 55% of Grade 5 students unable to read a Grade 2 English sentence, and 64% unable to perform basic arithmetic, according to the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER, 2021). These statistics highlight fundamental issues within the education system, including unqualified teachers, outdated curricula, and an overreliance on rote memorization. Nearly 40% of primary school teachers lack formal training or qualifications, which significantly impacts the quality of instruction and learning (Pakistan Education Statistics, 2021-22). Furthermore, the existing curriculum fails to incorporate modern skills such as STEM education, digital literacy, and critical thinking, leaving students ill-prepared for the demands of a globalized economy (UNESCO, 2023).

Infrastructure deficiencies exacerbate these challenges, creating an environment that discourages attendance, particularly for girls. According to Pakistan Education Statistics (2021-22), 41% of schools lack functional toilets, while 46% do not have access to clean drinking water. For female students, the absence of gender-segregated sanitation facilities becomes a major deterrent to continuing their education. Compounding these issues are natural disasters such as the 2022 floods, which destroyed over 27,000 schools and left millions of children without access to education (UNICEF, 2022). Recovery efforts have been slow, further delaying the reopening of schools and disrupting education for countless students.

Chronic underfunding remains a significant obstacle to addressing these challenges. Pakistan allocates only 1.7% of its GDP to education, far below the UNESCO-recommended 4-6% (UNESCO, 2023). This inadequate funding affects every aspect of the education system, from infrastructure development and teacher training to the provision of teaching materials and learning resources. Public schools, which serve the majority of Pakistan’s students, often operate without adequate financial support, widening the gap between public and private education. While private schools tend to offer better facilities and academic rigor, they primarily cater to wealthier families, further entrenching socioeconomic disparities (Zafar, 2022).

In addition to these systemic issues, gender disparities remain deeply ingrained in Pakistan’s education system. Cultural norms, early marriages, and a lack of safe transportation are among the barriers that prevent girls from accessing and completing their education. Economic constraints further exacerbate this problem, with families often unable to afford school-related expenses such as uniforms, books, and fees. Initiatives to promote gender equality, such as scholarships for girls and community awareness campaigns, have shown promise, but much more needs to be done to ensure that education is truly accessible to all (UNICEF, 2022).

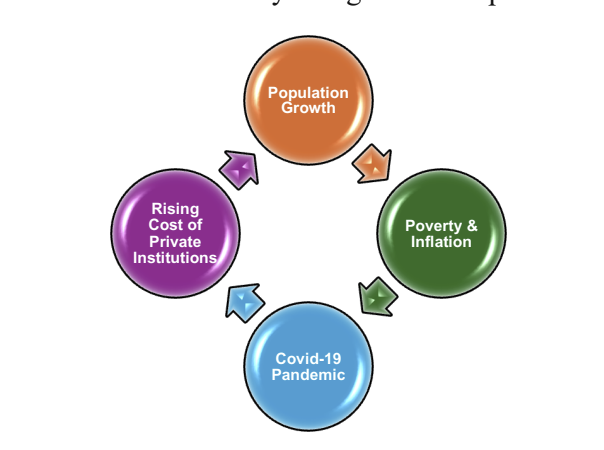

Pakistan’s education crisis is not merely a result of individual shortcomings but a reflection of systemic failures that require comprehensive and sustained reforms. Without addressing these underlying issues, the country risks further widening the gap between those who have access to quality education and those who do not. As a foundation for social and economic development, education must be prioritized through increased funding, teacher training, curriculum reform, and targeted interventions to address gender disparities and infrastructure deficits.

Proposed Solutions

Addressing the challenges in Pakistan’s education system requires a comprehensive and multi dimensional approach that targets systemic weaknesses while fostering equity, modernization, and accountability. One of the most pressing issues is the chronic underfunding of the education sector. Currently, Pakistan allocates less than 2% of its GDP to education, which is significantly below the UNESCO-recommended 4–6% (UNESCO, 2023). This underinvestment severely limits the country’s ability to address infrastructure gaps, train qualified teachers, and provide essential resources. Increasing the education budget to at least 4% of GDP would enable the construction of new schools in underserved areas, the renovation of existing facilities, and the provision of modern teaching aids, including laboratories and digital tools. Additional funding could also be directed toward targeted programs to improve access for marginalized groups, such as girls and students with disabilities, thereby promoting educational equity (World Bank, 2022).

Improving teacher quality is another critical aspect of reforming the education system. Teachers are the backbone of any educational framework, and their skills directly impact student learning outcomes. In Pakistan, many teachers lack professional training and are unprepared to adopt modern pedagogical methods. Comprehensive teacher training programs that emphasize student-centered teaching, inquiry based learning, and STEM education are essential for fostering critical thinking and creativity in classrooms. These programs should also equip teachers with the knowledge to integrate technology into their teaching practices, enabling them to utilize digital tools effectively (UNESCO, 2019). Furthermore, offering career advancement opportunities and performance-based incentives can help attract and retain talented individuals in the teaching profession, ensuring a higher standard of education across the country.

Gender disparities remain a persistent obstacle to achieving equitable education in Pakistan. Cultural norms, safety concerns, and economic pressures often prevent girls, particularly in rural areas, from attending school. Targeted interventions can address these barriers and promote gender equality. Providing scholarships for girls, offering safe and affordable transportation, and conducting community awareness campaigns can encourage families to prioritize girls’ education. Constructing gender segregated schools in conservative regions and hiring more female teachers can also help create environments where families feel comfortable sending their daughters to school. Research has consistently shown that empowering girls through education improves societal outcomes, including better health indicators, enhanced economic opportunities, and reduced poverty rates (UNICEF, 2021).

Modernizing the curriculum to incorporate essential 21st-century skills is crucial for preparing students to thrive in an evolving global economy. Pakistan’s education system must move beyond rote learning and focus on developing critical thinking, problem-solving, and digital literacy skills. STEM education should be prioritized, with subjects such as coding, robotics, and data analysis introduced at the school level to prepare students for careers in emerging fields. Additionally, life skills such as communication, teamwork, and adaptability should be integrated into lesson plans to equip students with the tools necessary to navigate an increasingly interconnected world (Ahmed & Ali, 2022). These curriculum reforms will help bridge the gap between education and the demands of the modern workforce, ensuring that Pakistani students are globally competitive.

To ensure the successful implementation of education reforms, robust monitoring and evaluation (M&E) systems are critical. Centralized and transparent mechanisms should be established to track the progress and impact of initiatives like the Single National Curriculum (SNC). Real-time data analytics on key indicators such as student performance, teacher attendance, and resource allocation can help policymakers identify gaps and refine policies to achieve better outcomes. Community feedback mechanisms and regular audits can further enhance accountability, ensuring that reforms lead to measurable improvements in learning (Pakistan Education Statistics, 2021).

Flexibility in the implementation of reforms like the SNC is equally important. While the SNC aims to standardize education across public, private, and madrassah schools to reduce disparities, rigid enforcement risks stifling innovation and reducing quality in high-performing private institutions. Allowing private schools, the flexibility to maintain higher academic standards while adhering to the core principles of the SNC can encourage innovation and academic rigor. This balanced approach would ensure that students across all school types receive a baseline quality of education while enabling private institutions to experiment with advanced teaching methodologies and extracurricular activities that enrich the learning experience (Zafar, 2022).

A multi-pronged approach that addresses resource allocation, teacher quality, curriculum modernization, gender disparities, and accountability is essential for transforming Pakistan’s education system. By increasing investment, empowering teachers, promoting equity, and fostering flexibility, Pakistan can build a robust and inclusive education system that equips its students for the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century.

Conclusion

The challenges facing K-12 education in Pakistan underscore deeply entrenched systemic issues, including chronic underfunding, gender inequality, infrastructure deficits, and governance inefficiencies. While efforts like the SNC represent an ambitious step toward reducing disparities and creating a unified educational framework, they come with significant risks if not implemented with nuance. Standardizing curricula across public, private, and madrassah schools aims to ensure equity in educational access and quality. However, concerns persist that a one-size-fits-all approach could inadvertently lower the academic standards of private schools, which historically operate at higher levels of rigor and innovation. Forcing private institutions to adopt a curriculum that may not align with their advanced teaching methodologies and resources risks compromising the quality of education offered in these schools.

Moreover, the SNC initiative must navigate the complexities of Pakistan’s diverse educational landscape. Public schools, private institutions, and madrassahs function in vastly different contexts, with varying levels of resources, teacher qualifications, and community support. Applying a uniform curriculum across these ecosystems without addressing their unique challenges could exacerbate existing inequities. In resource-limited settings, where infrastructure is poor and teacher training is inadequate, implementing the SNC without proper support risks creating further disparities in educational outcomes. Students in such settings may struggle to meet the standards of the SNC, widening the gap between urban and rural education systems and undermining the initiative’s goal of equitable access to quality education.

Additionally, the SNC rollout highlights the importance of stakeholder engagement and flexibility in education reform. Policymakers must prioritize feedback from educators, parents, and school administrators to ensure that the curriculum is adaptable to local needs while maintaining its core objectives. Failure to incorporate stakeholder perspectives risks alienating key actors in the education system, reducing the effectiveness of the reforms. Similarly, providing private schools with the flexibility to enhance the SNC with advanced coursework and innovative teaching methods can preserve their academic rigor while aligning with the broader goals of standardization.

To achieve the objectives of the SNC without compromising educational quality, significant investments in teacher training, infrastructure development, and monitoring mechanisms are essential. Equipping teachers with the skills and resources needed to deliver the curriculum effectively is critical for its success. Furthermore, robust monitoring and evaluation systems must be established to track the implementation of the SNC, address disparities as they arise, and ensure accountability at every level of the education system.

In conclusion, while the SNC holds promise as a tool for creating equity in education, its success hinges on careful implementation, responsive policymaking, and sustained investment in the broader education system. Addressing the structural issues that have long plagued Pakistan’s schools—such as inadequate funding, gender disparities, and outdated pedagogical practices—remains paramount. By adopting a holistic and inclusive approach, Pakistan can transform its education system into one that provides every child, regardless of socioeconomic background, with the opportunity to succeed and contribute to the nation’s progress.

References

o Ahmed, S., & Ali, Z. (2022). Challenges in integrating modern skills into education: Lessons from Pakistan. Journal of Educational Development, 18(2), 45–59.

o UNESCO. (2019). Teacher training for the future: Strategies for developing nations. Paris: UNESCO Publishing. https://learningportal.iiep.unesco.org/en/issue-briefs/improve-learning/teacher education-and-learning-outcomes

o UNICEF. (2021). Promoting gender equality in education: A case study from Pakistan. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/pakistan

o World Bank. (2022). Education sector analysis in South Asia: Opportunities and challenges. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://prisa.org.uk/research/the-state-of-education-in-south-asia challenges-and-proposed-solutions/

o Zafar, M. (2022). Balancing standardization and innovation: The case of Pakistan’s Single National Curriculum. Educational Policy and Reform Journal, 9(1), 32–47.

o Annual Status of Education Report. (2021). Annual Status of Education Report Pakistan. Retrieved from https://aserpakistan.org/index.php

o Government of Pakistan. (2012). Constitution of Pakistan Article 25-A: Right to Education. Retrieved from https://na.gov.pk

o Pakistan Education Statistics. (2021-22). Ministry of Education, Government of Pakistan. Retrieved from https://pie.gov.pk

o UNICEF. (2022). Out-of-School Children in Pakistan: Progress and Challenges. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/pakistan/education

o UNESCO. (2023). Global Education Monitoring Report 2023. Retrieved from https://gem-report 2023.unesco.org/

o World Bank. (2023). Learning Loss in Pakistan. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org